The Passion of the Carcass vs. the Corpus: Flesh vs. Body

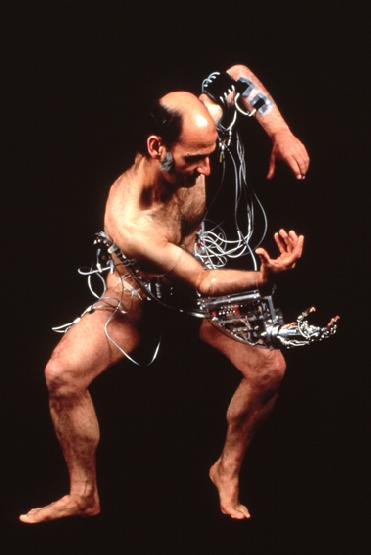

There is a difference between the body and the flesh, as Hortense Spillers has noted. What we consider to be the body is synonymous with legal personhood while the flesh (a category to which undistinguished black bodies, taken as a mass, are assigned) refers to the captive position that lies in opposition to all that the body represents. What Spillers describes as the “hieroglyphics of the flesh” refers to history imprinted on the body, which denotes one’s social standing. The phrase both recognizes the ‘realness’ of phenotypic expression, while it attempts to encapsulate all the non-biological influences that go into racial categorization. Such hieroglyphics, written by the moment of slavery and courts of law, collapse past, present, and future of both “marginalization as well as political agency,” in such a way that, “racism would land its blow on the body of the world for generations to come.”1,2

Civil War CDV of Gordon (slave) at the Baton Rouge Union camp during his medical examination. Photographers William D. McPherson and his partner Mr. Oliver, New Orleans, 1863. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

The idea of blackness is one through which we can examine the ways in which visible human traits, results of genetic expression, are things around which whole lores and events (the recollection and organization of which is called history) can be formed. For the black subject specifically, this particular codification resulted, post emancipation, in becoming caught in a ‘double bind’ between slavery (knechtschaft) and Leviathan (herrschaft). The logical telos of liberalism in its political mode is to construct categories of men which precede the individuals themselves. Rights follow the fluidity of Reason. The language of rights ablates contingent facts of time and place so that the liberal citizen is a pure category, a logic of citizen-making that awaits an input and produces an output. A constitution constitutes man-as-citizen; constitution-as-machine, as-logic. In this move towards freedom we moved from more direct forms of domination to being encouraged to self-regulate the body within liberalism.

In Testo Junkie, Preciado describes The Pill as an “edible panopticon,” an individual method of hormonal self-regulation in the form of birth control. In doing so, they offer a historical account of how this method of biopolitical administration, originally intended for use among white, suburban housewives, was the result of pharmaceutical data collected from Gregory Pincus and John Rock’s research trials for the contraceptive pill, Enovid, on low-income, Puerto Rican women in 1995.3,4 In these instances, the use-value of objectified flesh, or more precisely, the pain and discomfort of commoditized life sublimates erotic discharge for other mundane exercises of power. Such bodies have, historically, only been recognized within a eugenic framework geared towards the inhibition of psychic energy and disregard of one observable phenotype or subgroup in favor of the sovereign and its triadic model of the family. Preciado also notes that this Pavlovian regime of tease and denial usurps familial introjection and reconditions the libido to invest in, serve, and obey regulatory mechanisms of the disembodied panopticon—not anti-œdipus, rather, ultra-œdipus.

Within capitalism, the survival and life of the human is determined by forces of production. Marketing mechanisms exploit our unconscious and activate the death drive, the nature of which can be examined as our push towards wholeness beyond the limits of experience. These larger social systems activate processes such as our neural reward systems and help organize our drives, and these drives, taken outside ourselves, begin to solidify before us into social structures. Our bodily processes signal outputs towards the surrounding medium in which they are submerged in ways that are primordial and evolutionary (e.g., shortness of breath, sweating, etc.), but in this relationship between the body and its culture, routes of libidinal desire are also written, acts of symbolic exchange that link together these ‘responsive’ nodes to create patterned responses and narratives. Taken together, the external world to the proletariat is a machine environment. Hardly controlled by any one person, to navigate this environment is to understand how to live amongst the machine.

Ultra-Oedipus: Libido Recouped by The Imaginary

In order to explore the relationship between bodies, sexuality, and technology, we could attempt to fathom a world in which sex robots with advanced AI capabilities were made for mass production and distribution, creating easy access to ‘intelligent’ and responsive toys made explicitly for the purposes of human sexual desire. Presently, because prototypes of such technology keep us from examining a significant enough number of individuals due to the inherently discriminatory nature of capital acquirement, we must break down this argument into smaller components by examining the nearest available analogs. While AI sex bots do not yet exist beyond the prototype stage, ‘life-like’ sex dolls do, and, separately, companies and researchers are attempting to perfect artificial technology, most notoriously through the use of home technology such as Alexa, and through social media platforms like Facebook.

What happens between the purchaser of a sex robot and the toy during copulation is an act of play which pairs the organic with the synthetic. Such displays of desire can find their siblings in BDSM ‘play,’ specifically within sadomasochistic exchanges, and also within the world of porn. BDSM could be understood, in some respect, as adding non-procreative erotics and an element of play to the act of sex. Here, ‘BDSM’ and ‘porn’ are meant in more figurative terms, away from their normative connotations. The former refers to the idea of sexual play and an exploration of power dynamics in the broadest sense, and the latter to images, writing, or art (collections of symbols) intended to arouse. Though typically thought of as outside of society-at-large, elements of BDSM can be found in mainstream porn films and popular society, and ‘vanilla’ society contains fetishes as well, just those that are deemed normative. Thus the question of Artificial Sexuality forces an exploration of what it means to have a pornographic imagination, because the basis of what comes from exercising these faculties, which ultimately engender semi-solidified imaginaries, are the result of libidinal outputs from our bodies as desire-producing machines.

Attitudes towards technology within popular discourse can sometimes veer towards overzealous optimism or technophobia. Visions of the future, whether dystopian or utopian, are anticipations of that which is ‘not yet.’ However, such visions can (particularly when represented in film, literature, or art) also function as critiques of a present state or historically situated forewarnings. Thus, it is difficult to envision a future that is not, at least somewhat, influenced by the particular time in which the schema was made. We cannot overlook how technology is a byproduct of social ingenuity and labor, and might embody the frameworks of a culture by design.

It is only through a thorough analysis of how political subjects are socially and historically constituted that we may understand how traces of libidinal desire become rerouted and encoded on subjects, and how this eventually comes to form recognized collectives that are codified and categorized. We should make a distinction between the idea of culture in the social sense and culture in the biological sense. In the social sense, culture is the accumulation of semiological objects and social artefacts (language, signs, customs, etc.) among a linguistic species within a specific geography and epoch. Culture is what Sylvia Wynter referred to as an “autopoetic turn” toward the sociogenic from the phylogenetic and ontogenetic, dormant objects animated by cross-pollination over a timescale (history)—simultaneously, a replicative process and an archive, which elucidates the relationship between the material production of life (zoe-bios) and the virtual production of information (logos-mythos).5 Cultural reality is not an inert system of signs; rather, such symbols orient our understanding of reality. Therefore, paying attention to symbols is the basis of a narrative: that it makes itself real. Rather than being in a binary of real vs. not-real, a narrative conjures approximations of reality in degrees of making-it-real.

Mnemo-Libidinal Inscriptions: The Erotics of Temporality and the Alien Power of Capital

The power of collective memory lies not in the memories themselves but rather in how they haunt and manipulate the future, like specters. The ghosts that haunt us the most are not the metaphysical remains of people who have died but rather the past, collective experiences that have burrowed into the cavernous unconscious, and which seek to feed and maintain themselves there. All organic animated things are composed of inorganic matter which self-organizes through chemical and physical processes, and culture itself can be seen in a similar light as a self-organizing system composed of bodies. There is a reciprocal relationship between the body and its culture, which functions as the primary site of politics. The more one alters the culture within which the body is submerged, the more the body is presented with a variety of environmental ‘selective pressures.’ In this process, the body’s awareness of what it considers the world to be is altered. Moreover, some instances that we consider to be an essential biological state of affairs are little more than mythos, a vulgar understanding of the mechanisms within the body. Beyond cultural speculations and narrative, there is a relationship, and at times a tension, between our biological processes and social life.

As we interact with technology, we change the medium in which we exist, which, in turn, modifies the ways in which we engage with others and view ourselves as subjects, sometimes in ways that we can foresee, and sometimes in ways that are unbeknownst to us. If we view technology not just in instrumental terms but as cybernetic processes of self-organization, then capitalism can be seen as a technology out of which bodies are formed, organized, and shuttled around in particular ways. These different social structures correspond to specific libidinal patterns, and technical infrastructures of 21st -century capitalism have intensified this cybernetic mode of organization. As we recognize changes to our bodies and minds, due in part to feedback loops between us and the technologies we engender, we understand our future selves as alien to the present. Looking into the future, we anticipate a gradual sort of ego-death which arises out of acts of symbolic exchange, the particularities of which are influenced by biological and cultural forces and facilitated or amplified by computational infrastructures.

In this view, we can ask: What do we mean when we say, “I feel the same” or “I feel different?” “How do I feel respective to the other selves I have been?” The operational dynamic here is that of time.6 In the movement from organic to synthetic, the growing intimacy between humans and machines deepens. Typically, in order to make such statements, one points to ideas like the notion of accelerating technological change to claim that more ‘advanced’ or complex technology will close the gap between psyche and machine. Yet, we can also argue that over time, as we begin to integrate more kinds of technology into our social lives and increasingly use it to mediate interactions between us, we begin to change our perception of what is human-like. Over time we unknowingly crawl ourselves closer to a more muddled definition of that which is mechanistic by lowering our standard for what that entails.

Normative temporality is organized as the linear passage of three domains: past, present, and future. The ‘future’ then, is a perceived endpoint that exists as a possible outcome of a set of given relations. Our relationship to the idea of the future is that while it appears as new, it is really the culmination of collective will that creates a narrative out of a genealogical set of relations that are determined to have come before. It is seen as a ‘natural’ progression from said events as an endpoint, but is really also the picture of a particular collective desire. It might be more accurate to refer to what is colloquially known as the future as ‘that which is not yet,’ an infinite number of possibilities that confront us.

Modern secular society presents us with a vision of freedom through individualism, yet it simply confronts us with new versions of the divine. Capital, accumulated Value, acquires its own autonomy. Capitalism masks the intricate social relations that constitute our being. A product is something made by the labor power or some ‘we’ but when one encounters it in the form of the commodity fetish, these relations are obscured. Under capitalism, our social relations are centered around the production of commodities and economic exchange and, as such, Capital-mediated relations appear to us as having objective forms of value. In its alien drive to reduce socially necessary labor time, capitalism institutes specific forms of spatial and temporal organization of behavior (e.g. regimes of repetitive labor tasks, categorization, calculation, probabilistic risk assessment, facial recognition) all underlain by automation and exchange.7 The circulation of Capital is a continuous one that ‘calls for’ and is accompanied by cultural myths that substantiate a progressive notion of history. Within this mode of production, technology serves a particular role within the labor process, which is to increase productivity.

Synthetic Bondage: Libido Recouped by The Synthetic

It is generally understood that suspension of disbelief is an intrinsic component of enjoying pornography. However, our understanding of the actual nature of sex work as it pertains to the production of pornographic films is also obscured within capitalism. Liberalism as a system in which one must argue for private rights, publicly,8 constructs narratives around pornographic actors that tend to shy away from making comparisons between sex work and ‘real’ or ‘civilian’ work, and colloquially, pejoratives are sometimes used to delineate between those who are chaste and those who are depraved. We can simultaneously grant the notion that prostitution is “the world’s oldest profession,” meaning it predates capitalist exchange, while also examining how and why this occupation manifests through history despite its marginal status, much as we can both recognize that slavery as a concept has existed throughout recorded history, while still examining the particulars of chattel slavery because of what surrounded it. Much like in other, more socially acceptable jobs, elements of the true nature of mainstream pornographic production (particularly that it requires hours of arduous labor to produce a scene) are obscured under the socioeconomic paring that engenders the fungible elements of the capitalist world.

Performer Anikka Albrite’s movements digitally rendered as a virtual image via Camasutra VR’s motion capture studio. 2017.

Capitalism hijacks our sensibilities by instrumentalizing our cognitive blind spots and our tendency to manufacture meaning though the mediation of symbols and images. These images often confront us in the form of advertising, yet this is not the only way in which this spectacle takes shape. Capitalism itself bets on its ability to be a producer of desiring forces and a conduit for libidinal investments. Tapping into this productive power, however, comes at a cost. In this case, organic material is sacrificed towards the creation of synthetic machine-like intelligence. These cybernetic processes work similarly to the process of neural conduction: collection of the signal, integration of the signal, and distribution of the processed information. But if the constitution of the cybernetic signal is understood in libidinal terms, the muck that this signal is drawn from can also serve as the site of repression, sublimation, and jouissance.

The death drive is dissipation of libidinal intensity, the material expenditure of energy and time within the space of reality. Picture billions of substrata, each one a cell containing units of residual solar energy, irrepressible impulses contained within a body or a form. The flows of these substrata, bodies, or forms create differentiating fusion and exchange, expending this energy via the transduction of labor.

The wretched and the sordid are in fact essential to the attainment of the sublime…Masochism is a movement which integrates the lowest impulses with the highest; it is a story about falling in order to ascend.9

Davecat, one of the most prominent advocates of ‘synthetic love,’ lives with two real dolls, Sidore, whom he considers to be his wife of over 15 years, and Elena, who is both his mistress and Sidore’s girlfriend. When asked about meeting his silicone wife for the first time, he noted, “It seemed perfectly normal for me to treat something that resembles an organic woman the same way I’d treat an actual organic woman.”10 Moreover, what makes Davecat interesting is that, while he calls his experience “natural,” he does not pretend that his dolls are human, and in fact claims that Sidore’s charm lies, for him, in the fact that she is partially synthetic.

Davecat, in an attempt to express his ideal form of romantic and sexual desire, brushes up against the uncanny valley to an extent that might make many uncomfortable, yet he still prefers this lifestyle more than relationships with organic women because he is self-admittedly risk averse when it comes to taking emotional chances. In order to avoid the pain of breaking up with a long-term partner, Davecat would rather opt for the ease of a relationship with his “perfect partner.” However, even Davecat’s carefully constructed universe is not without pain. In regards to making repairs to his synthetic wife, he confesses that, “When her body comes close to falling apart through entropy, I’m pretty cut up about it, as anyone would be when facing the mortality of a loved one.”11 Ultimately, though one could argue that the introduction of such robots on a mass scale might be beneficial for some, especially introverts, we must note that even within our alternatively constructed solutions, we may never escape certain unpleasant experiences, like those related to anxiety and dread.12

The internet’s progressive infiltration of real space is representative of our movement towards the inorganic recuperation of libido, as it represents a latency path that facilitates communication between physical objects. Increasingly, as improvements are made to the network, more hardware is shed or made more compact. Though early conceptions of the internet latched on to terminology that represented the interconnectedness of its users, like the ‘hive mind,’ it was naive to think that use of such technology, particularly in social media interactions, could escape the medium in which it was used. Technology, here loosely defined as both tools and epistemological processes, is altered and molded by the methods which surround it while it also facilitates circuits for the libidinal energy it draws from. While social media has the ability to link users globally, it has also intensified myopic ways of seeing by presenting users with the ability to ‘choose’ their content. The internet actually singularizes the spectacle into one feed.

There exists a relationship between the subject’s pornographic imaginary and the political sphere, with the former being a vulgar reflection of the latter. Pornography (which in this instance refers to images, items, and subjects associated with the sex trade) functions as a receptacle for hidden desires. Though the deviant fantasies associated with such images and symbols are seen as verboten in the surface of our daily lives, such a view obscures the alien nature of what occurs within our day to day experience where we transcribe our desires into symbols, tracing threads of socio-historical narratives. In a sense, politics is how an agent chooses to construct their subjectivity, and thus is about the collage of internal objects that subjects choose to openly show to others (or feel they must adhere to) within the public sphere. Much like in the relationship between the white collar realm and the economic underworld, constructed symbols that circulate within extrinsic systems that we encounter create their antithesis from which an underbelly is formed. Here, pornography is not only the ‘publification of the private,’ but a technology of pleasure that conceals its public constitution. Additionally, though some of the language that is related to pornography and sexuality links the idea of pleasure to normative ideas of what is ‘good,’ unfavorable experiences such as pain and violence are inseparable from the pornographic imagination.

Libido Recuperated by The Pornographic

Despite the ability that Sade has had to perpetually shock and disgust many readers, one could argue that his stories, in fact, lack sexual abandon. Clinical and methodical, his description of sexual acts is typically removed and matter of fact. Andrea Dworkin unintentionally illustrates this point in her harrowing description of Sade and his real-life misdeeds. In Pornography: Men Possessing Women, Dworkin dedicates an entire chapter to the author, and within it, she spends most of it depicting Sade’s real-life predilection towards acts of violence and degradation, as opposed to providing an in-depth analysis of his work. To make him seem as unsavory as possible Dworkin finds she must depedestalize him and posits that, “In Sade, the authentic equation is revealed: the power of the pornographer is the power of the rapist/batterer is the power of the man.”13

From there, she offers an analysis of Bataille’s work, which is often lumped into the same transgressive cadre as Sade. She refers to this kind of text as “high class literary pornography,” or works in which force and violence are thought to be laden with meaning because they bring one closer to death. She notes:

The violence of death is the violence of sex, and the beauty of death is the beauty of sex, and the meaning of life is only revealed in the meaning of sex, which is death. The intellectual who loves this kind of pornography is impressed with death.14

An argument that runs throughout Dworkin’s text is that pornography encourages men to eroticize the humiliation of women as a psychological act of retaliation because her status as the sexual object of male desire subordinates men to their own desires, which they project onto the performance of femininity. This illusory feeling of temporary powerlessness is one way in which the man comes to resent the woman. We may grant this argument at least some partial truth in the sense that it expresses the idea that relationships between individuals categorized as groups are structured by historical processes, social and economic factors, and could possibly even agree with her comments about the fascination with death among “high class literary pornographers” like Bataille (something that he would probably agree with, to an extent). Still, if we look at those that have cited Dworkin since, one could argue that there is a particular kind of thinker who is obsessed with Dworkin’s notion of sexuality because it poses a theoretical challenge to their own. Her depiction of pornographic works become perversely intriguing because, in an effort to appall, Dworkin unintentionally writes salacious accounts which work to entice a certain type of sadist.

For all the unpleasantries that Dworkin’s conception of gender presents, we must keep in mind that positing a particular brand of humanism as a retort to such concerns can sometimes be a nefarious, albeit subtle, way of preserving pre-existing norms. When examining pornography clinically, we can note that, while a certain fantastic quality is a prerequisite for enjoyment, a certain level of realism must also be maintained. In other words, if we conceptualize pornographic work as a collage of symbols, we can note that the components of that picture, the objects,15 that make up a pornographic scene must also be granted a certain degree of ‘reality’ in order for such scenes to work as well. For instance, a scene between a stepmother and son only works if we first have a conception of what such objects or social relations, as they are presented to us within the world, denote. However, because this ‘reality principle’ is, in some cases, the result of libidinal processes underlying the symbolic organization of perception, it is common to fetishize, in private, ideas that we would rally against within the public sphere.

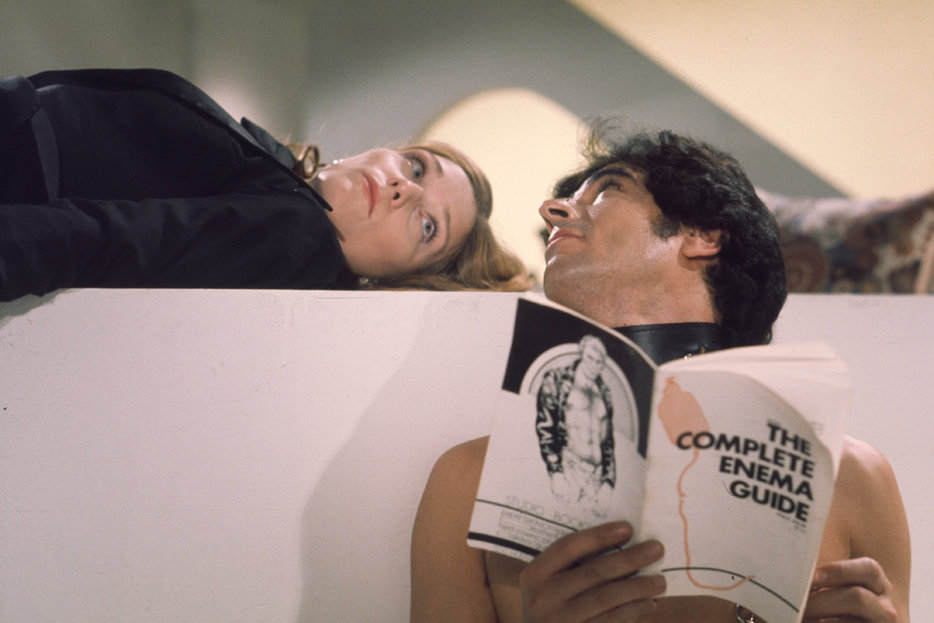

Jamie Gillis and his “On the Prowl” series of pornographic films can be seen as improvisational works of acting that function as a meta-commentary on the medium of film and on the content of pornography. In these gonzo works, Gillis approached various men with the premise of being able to have sex with a porn star (typically amateur) for free. The charm of these films—though they display women, and sometimes Gillis himself, being humiliated and degraded—lies in the method they use to utilize pornographic imagination. Gillis, in actively trying to convince the average consumer of porn to become part of the staged act itself, blurs the boundary between the voyeur and exhibitionist. This format presciently comments on, or speculatively realizes, the period of ‘reality pornography’ which followed. What’s important is that neither does Gillis try to couch his videos under the guise of art, nor are his videos presented as one-dimensional and flat “attempts to pawn off abused women to pervy men.” Instead, he interjects himself as a willing participant in many films as well, and lets the actresses or actors expose their lines of thought to him. In these exchanges, Gillis helps show that sexual desire, humiliation, and guilt are bound to one another, as he acts as a priest, or documentarian, simultaneously jealous and pious.

Still from Radley Metzger’s The Opening of Misty Beethoven, erotic retelling of George Bernard Shaw’s classic play Pygmalion, directed by Radley Metzger, 1976, USA, 86 minutes, starring Jamie Gillis, Constance Money and Jacqueline Beudant.

More so than a fascination with death itself, sexual impulses and libidinal desires follow a death drive, or in other words, such flows ultimately veer towards ego death. For example, cuck porn typically depicts a scene where a man (usually white) watches his wife (also usually white) have sex with another man (who is usually black). Beyond the knee-jerk emotional reactions one may have to the idea of a black body being “animalized” in such a way, such scenes give us important insights into the collective imaginary of which we are a part. While such fantasies reenact the violence of racialization and sexualization at one level, these imagined scenarios reveal that the true desire staged in the scene of cuckoldry (rehearsal of the debasement of a privileged term within the political-philosophical binaries which constitute the ways in which we see and classify subjects) is a desire to abolish the self. In this way, pornography helps expose unconscious desires that structure our sense of self, and reveals that our death fetish may be better rephrased as pertaining to a libidinal economy that must constantly ward off excess through the sacrifice of an ‘accursed share’ that is profoundly linked with our fascination with ‘filth.’16 This is particularly true in modern liberal secular society, which functions on a particular kind of atomization that, while based on information and communication technologies, in fact drives us further from one another. We are obsessed with both the nature of our moral corruption (though the way in which this plays out and even this concept of sin is upheld by a particular Christian lens through which the Western world has been shaped) and we are obsessed with subterranean aspects of the libidinal economy that our desires have helped form.

Humans are caught in a cognitive catch 22, limited in that they can neither fully understand another subject except through a symbolic mediator nor can they fully apprehend the complex continuum that constitutes the Self. We are automatons in a very literal sense, since so many of the body’s functions would fail if they were voluntary, and it is only through the use of language between ourselves and others that our emotions and cognition can be examined. Because of these gaps in egocentric cognitive models, true death of the self is an experience that lies outside the realm of that which we can cognitively and rationally describe, yet we are inextricably bound to this pursuit. Our propulsion towards ego death is the result of a lapse in our ability to fully perceive our selfhood in its entirety (the transparency of the phenomenal self-model).17 Though our current techno-social medium nudges us towards atomization, it obscures the fact that our ‘self’ is formed through reciprocal relations with others, and thus our push towards a unified comprehension of the self is bound up with those libidinal processes constituting the technics and erotics of the self, and those epistemological transitions and synthetic gluings between that which is organic and inorganic.

Restoration of the Libido

In a historic letter, an adolescent Arthur Rimbaud wrote, “Je est un autre,” which translates to “I Is another” or “I Is Somebody Else.” The uncanny beauty and horror of these few words lies in their phraseology, in that they are fundamentally grammatically incorrect. If Rimbaud meant to say “I am somebody else” he would have written “Je suis un autre.” The use of est suggests an objectification of self that suis could not convey, because est like the English is can only be used in this way as regarding something other than oneself. We say such things as that is, it is, she is, life is, time is, and desire is but never I is because we otherwise would be committing a cultural faux pas whose consequence is perceived ignorance. From birth, children are immersed in complex grammatical structures which convey a sense of distinct separation of self from society as a whole—a separation which isn’t really there. At the same time, we accept we are as our one and only tool for attaching ourselves to an outsider or to a whole. By saying I is another Rimbaud rejects the notion that he is a self outside this other.